Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

Even if we might think that something ‘just is’, and that there is a single version of events or way of doing something, most aspects of our daily lives can be seen in different ways, from different perspectives.

This includes even something as simple as the colour of an item of clothing.

In his book How Minds Change, David McRaney tells the story of how Cecilia Bleasdale sent a picture to her daughter of the dress Cecilia was planning on wearing at the daughter’s wedding. McRaney writes how the daughter and her husband couldn’t agree on what they saw -

“...so they asked their friends to settle the argument. What colour do you see? Instead, the argument spread to their friends, then their friends’ friends, and so on. Some people saw black and blue, others saw white and gold…”

McRaney describes how this disagreement over the colour of the dress became “the debate that broke the internet” (quoting NPR in the US) -

The hashtag #Dress appeared in 11,000 tweets per minute and an article published on Wired.com received 32.8 million views in the first few days.

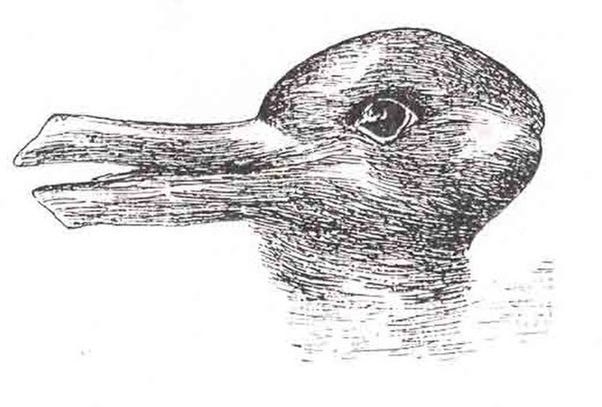

What do you see: duck or rabbit?

Perhaps the most famous example of our human ability to see things in different ways is the Rabbit-Duck Illusion, where some people see a duck with its beak slightly open, and others see a rabbit with its ears back.

The practice of law abounds with examples of seeing things in different ways. To give one example that comes to mind, in the English case of Uber v Aslam, the issue was whether Uber drivers work for Uber under workers contracts (and so qualify for workers rights under employment laws), or are independent contractors and work for themselves (and so don’t benefit from these rights):

One way of looking at the role of Uber drivers was, because they drive their own vehicles and are free to work whenever they want, and the Uber app creates a contract between the driver and a customer (with Uber merely acting as a booking tool and charging a fee for using the app), that they are independent contractors.

Another way of seeing the circumstances is that because Uber sets the fare (calculated by the app), because the Uber app monitors drivers’ rates of acceptance of rides (and logs drivers out of the app if they reject too many), and asks passengers for ratings on drivers and then gives drivers warnings if these are below average (which can lead to termination of their use of the Uber app), that the drivers work for Uber.

(In that case, the UK Supreme Court decided that the second way of looking at the facts carried more weight and so sided with that.)

We live life not as it is but as we see it

This is a misquote of Steven Covey, author of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

Covey tells a story in that book of how he was once riding the underground train in New York on a calm morning when some children entered his carriage and started messing around and being very loud. Covey writes how he became more and more irritated at the children’s behaviour, and how he could see other passengers on the train having similar reactions. And yet the children’s father seemingly did nothing to stop his kids from “yelling back and forth, throwing things, even grabbing people’s papers.” Covey eventually went over to the man and said something; he describes in the book the father’s response:

“The man lifted his gaze as if to come to a consciousness of the situation for the first time and said softly. ‘Oh, you’re right. I guess I should do something about it. We just came from the hospital where their mother died about an hour ago. I don’t know what to think, and I guess they don’t know how to handle it either.’”

Covey tells in the book how, in that moment, his view of the situation instantly changed:

“Suddenly I saw things differently, and because I saw differently, I thought differently, I felt differently, I behaved differently…”

Our perception changes our effectiveness

Since this is a blog about how lawyers work, in light of the above examples it seems fair to say that our actions as lawyers (and as people) depend on our perception (whether of a set of circumstances, a person, a text, or something else). It is our choice of actions which determines our performance and effectiveness, and in order to guide those decisions, we need to be aware of how we are seeing a particular situation.

In the Amazon Prime series All or Nothing: Arsenal (a behind-the-scenes documentary on Arsenal Football Club), club manager Mikel Arteta refers to the Rabbit-Duck Illusion as an example of how we can see things in different ways, and highlights how his job as a manager is to make sure the team see the game they are looking to play in the same way:

“My only aim is that everyone is seeing the duck, or the rabbit. Because if you see the duck and I see the rabbit, we are on a different path, we’re in a different direction.”

Just as wearing different glasses with different lenses (for example, sunglasses, reading glasses or distance glasses) affects the way we see everyday life and affects our experience of life, so our wearing of different metaphorical lenses in the practice of law determines our ability to see things in different ways and so our experience and effectiveness as lawyers.

We practice law not as it is, but as we see it. The effective lawyer has the ability to wear different lenses and choose the right lens at the right time.